Few ideas capture the collective human imagination more powerfully than the notion of a “universal library”—a singular repository of all recorded knowledge. From the grandeur of the Library of Alexandria to modern digital initiatives, this concept has persisted as both a philosophical ideal and a practical challenge. Miroslav Kruk’s 1999 paper, “The Internet and the Revival of the Myth of the Universal Library,” revitalizes this conversation by highlighting the historical roots of the universal library myth and cautioning against uncritical technological utopianism. Today, as Wikipedia and Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT emerge as potential heirs to this legacy, Kruk’s insights—and broader reflections on language, noise, and the very nature of truth—resonate more than ever.

The myth of the universal library

Humanity has longed for a comprehensive archive that gathers all available knowledge under one metaphorical roof. The Library of Alexandria, purportedly holding every important work of its era, remains our most enduring symbol of this ambition. Later projects—such as Conrad Gessner’s Bibliotheca Universalis (an early effort to compile all known books) and the Enlightenment’s encyclopedic endeavors—renewed the quest for total knowledge. Francis Bacon famously proposed an exhaustive reorganization of the sciences in his Instauratio Magna, once again reflecting the aspiration to pin down the full breadth of human understanding.

Kruk’s Historical Lens

This aspiration is neither new nor purely technological. Kruk traces the “myth” of the universal library from antiquity through the Renaissance, revealing how each generation has grappled with fundamental dilemmas of scale, completeness, and translation. According to Kruk,

inclusivity can lead to oceans of meaninglessness

The library on the “rock of certainty”… or an ccean of doubt?

Alongside the aspiration toward universality has come an ever-present tension around truth, language, and the fragility of human understanding. Scholars dreamed of building the library on a “rock of certainty,” systematically collecting and classifying knowledge to vanquish doubt itself. Instead, many found themselves mired in “despair” and questioning whether the notion of objective reality was even attainable. As Kruk’s paper points out,

The aim was to build the library on the rock of certainty: We finished with doubting everything … indeed, the existence of objective reality itself.”

Libraries used to be zero-sum

Historically,

for some libraries to become universal, other libraries have to become ‘less universal.’

Access to rare books or manuscripts was zero-sum; a collection in one part of the world meant fewer resources or duplicates available elsewhere. Digitization theoretically solves this by duplicating resources infinitely, but questions remain about archiving, licensing, and global inequalities in technological infrastructure.

Interestingly, Google was founded the same year as Kruk’s 1999 paper was nearing publication. In many ways, Google’s search engine became a “library of the web,” indexing and ranking content to make it discoverable on a scale previously unimaginable. Yet it is also a reminder of how quickly technology can outpace our theoretical frameworks: Perhaps Kruk couldn’t have known about Google without Google. Something something future is already here…

Wikipedia: an oasis island

Wikipedia stands as a leading illustration of a “universal library” reimagined for the digital age. Its open, collaborative platform allows virtually anyone to contribute or edit articles. Where ancient and early modern efforts concentrated on physical manuscripts or printed compilations, Wikipedia harnesses collective intelligence in real time. As a result, it is perpetually expanding, updating, and revising its content.

Yet Kruk’s caution holds: while openness fosters a broad and inclusive knowledge base, it also carries the risk of “oceans of meaninglessness” if editorial controls and quality standards slip. Wikipedia does attempt to mitigate these dangers through guidelines, citation requirements, and editorial consensus. However, systemic biases, gaps in coverage, and editorial conflicts remain persistent challenges—aligning with Kruk’s observation that inclusivity and expertise are sometimes at odds.

LLMs – AI slops towards the perfect library

Where Wikipedia aspires to accumulate and organize encyclopedic articles, LLMs like ChatGPT offer a more dynamic, personalized form of “knowledge” generation. These models process massive datasets—including vast portions of the public web—to generate responses that synthesize information from multiple sources in seconds. In a way this almost solves one of the sister aims of the perfect library, perfect language, where the embeddings serve as a stand in for perfect words.

The perfect language, on the other hand, would mirror reality perfectly. There would be one exact word for an object or phenomenon. No contradictions, redundancy or ambivalence.

The dream of a perfect language has largely been abandoned. As Umberto Eco suggested, however, the work on artificial intelligence may represent “its revival under a different name.”

The very nature of LLMs highlights another of Kruk’s cautions: technological utopianism can obscure real epistemological and ethical concerns. LLMs do not “understand” the facts they present; they infer patterns from text. As a result, they may produce plausible-sounding but factually incorrect or biased information. The quantity-versus-quality dilemma thus persists.

Noise is good actually?

Although the internet overflows with false information and uninformed opinions, this noise can be generative—spurring conversation, debate, and the unexpected discovery of new ideas. In effect, we might envision small islands of well-curated information in a sea of noise. Far from dismissing the chaos out of hand, there is merit in seeing how creative breakthroughs can emerge from chaos. Gold of Chemistry from leaden alchemy.

Concerns persist, existence of misinformation, bias, AI slop invites us to exercise editorial diligence to sift through the noise productively. It also echoes Kruk’s notion of the universal library as something that “by definition, would contain materials blatantly untrue, false or distorted,” thus forcing us to navigate “small islands of meaning surrounded by vast oceans of meaninglessness.”

Designing better knowledge systems

Looking forward, the goal is not simply to build bigger data repositories or more sophisticated AI models, but to integrate the best of human expertise, ethical oversight, and continuous quality checks. Possible directions include:

1. Strengthening Editorial and Algorithmic Oversight:

- Wikipedia can refine its editorial mechanisms, while AI developers can embed robust validation processes to catch misinformation and bias in LLM outputs.

2. Contextual Curation:

- Knowledge graphs are likely great bridges between curated knowledge and generated text

3. Collaborative Ecosystems:

- Combining human editorial teams with AI-driven tools may offer a synergy that neither purely crowdsourced nor purely algorithmic models can achieve alone. Perhaps this process could be more efficient by adding a knowledge base driven simulation (see last week’s links) of the editors’ intents and purposes.

A return to the “raw” as opposed to social media cooked version of the internet might be the trick afterall. Armed with new tools we can (and should) create meaning. In the process Leibniz might get his universal digital object identifier after all.

Compression progress as a fundamental force of knowledge

Ultimately, Kruk’s reminder that the universal library is a myth—an ideal rather than a finished product—should guide our approach. Its pursuit is not a one-time project with a definitive endpoint; it is an ongoing dialogue across centuries, technologies, and cultures. As we grapple with the informational abundance of the digital era, we can draw on lessons from Alexandria, the Renaissance, and the nascent Internet of the 1990s to inform how we build, critique, and refine today’s knowledge systems.

Refine so that tomorrow, maybe literally, we can run reclamation projects in the noisy sea.

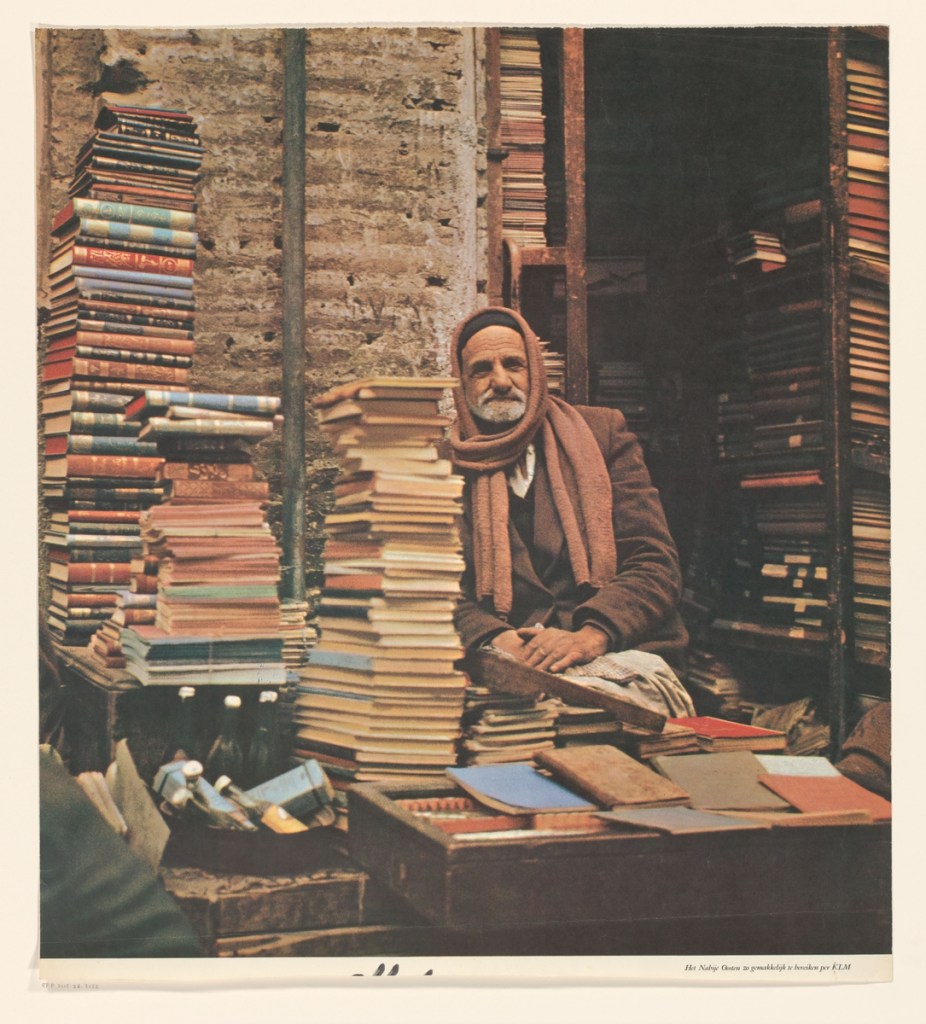

Image: Boekhandelaar in het Midden-Oosten (1950 – 2000) by anonymous. Original public domain image from The Rijksmuseum

Leave a comment