I. Everything is a Balinese Cockfight

It was after a police chase and a conspiratorial lie that Clifford Geertz and his wife Hildred were accepted into the social fabric of 1958 Bali. Until then they had been ignored, a treatment reserved for intruders. The police chase was the aftermath of attending a cockfight recorded in Geertz’ essay, Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight. The cockfight, a ritual with the stakes so irrationally high that they ceased to be about money (or the birds) at all. Status, dignity, and the honor of their kinship groups was all on the table. It was deep play—a game where the potential for loss so catastrophic, and the potential for glory so fleeting, that from a utilitarian perspective, it was madness to engage in it at all.

We have built a global version of this village. If one looks at the architecture of our current digital existence, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that we are all, perpetually, standing around the ring of a Balinese cockfight. Preparing and shaping our identities for the battle box of social media. Every post is immediate participation with unbelievably high stakes. Social media is place to bet on one’s own standing in the hierarchy. We have gamified human interaction to such a degree that the simple act of being has been replaced by the exhausting labor of performing.

This is why the silence has descended. It is not that we have nothing to say, but that the cost of saying it has outstripped the value of the connection. When every interaction is a deep play scenario the rational response is to stop playing. The open web, once promised as a boundless library or a global town square, has revealed itself to be a panopticon where the guards are also the prisoners, and everyone is armed with a scorecard.

The tragedy of this arrangement is not just the anxiety it produces, though that is significant. The tragedy is the loss of the middle layer of human experience. Geertz noted that the cockfight was a dramatization of status concerns, a way for the Balinese to tell a story about themselves to themselves. In our digital translation of this ritual, we have similarly flattened the world. The fox, an animal defined by its ability to navigate the undergrowth and find hidden paths, cannot survive in the center of the ring. The ring is designed for the hedgehog—the creature who knows one big thing and defends it with bristles. And so, the fox looks at the high-walled arena, sees the blood on the sand, and quietly slips away toward the tree line.

II. The Gunpowder Empire of the Mind

To understand why the open plain has become uninhabitable, we must look backward to the last time the world was reorganized by a sudden explosion of reach. Historians speak of the Gunpowder Empires—the Ottomans, the Safavids, the Mughals—who used the new technology of artillery to consolidate vast territories under a central authority. This required an administrative transformation. Gunpowder required money, and money required the translation of land into a legible, taxable asset. The loose, overlapping rights of the medieval village—where one man might own the fruit of the tree, another the right to graze beneath it, and a third the right to cross the field—were swept away. The state needed to know who owned what, exactly, so it could extract its due. Land became an abstract asset, a polygon on a map that could be bought, sold, and taxed without anyone ever touching the soil.

We are living through the rise of the Gunpowder Empires of the Mind, a new nature. Just as the early modern states needed to simplify the land to tax it, the High-Tech Modernist platforms of Silicon Valley need to simplify thought to monetize it. They are engaged in a project of radical legibility. A wandering thought is of no value to an algorithm since it cannot be categorized. A complex relationship is inefficient and creates friction in the social graph.

This is the war between Metis and Techne, a distinction drawn by the political anthropologist James C. Scott and the philosopher Isaiah Berlin. Techne is the knowledge of the system-builder, measured and protocolized. Techne is the language of the algorithm. It assumes that the world is a stable set of variables that can be optimized. It is the worldview of the Hedgehog, who relates everything to a single central vision—in this case, the vision of engagement metrics and ad revenue.

Metis, on the other hand, is the knowledge of the Fox. It is cunning, local, and slippery. It is the knowledge of the sailor who knows how to read the ripples on the water to find the current, or the peasant who knows which patch of soil stays wet longest in a drought. Metis cannot be simplified into a manual or a code base because it is dependent on the specific, shifting context of the now. It survives in the thicket—the messy, unmapped reality of lived experience.

The Gunpowder Empires of the Mind have declared war on Metis. They seek to pave over the thicket to create a smooth, frictionless plain where data can flow unimpeded. They want us to be Hedgehogs—consistent, predictable, and branded. They ask us to niche down, to define our vertical, to become thought leaders in a specific domain. They are trying to turn the messy ecology of human curiosity into a plantation of cash crops. The fox, with its long tail dragging through the mud of a thousand different interests, finding connections between a 17th-century poem and a 21st-century software bug, is an error in their system. The fox is illegible. And because it is illegible, it is being hunted.

III. The Dark Forest as a PTSD Response

It is no wonder, then, that we see a mass migration away from the center. Yancey Strickler and others have called this the Dark Forest Theory of the Internet, borrowing from Liu Cixin’s sci-fi axiom that in a universe full of predators, the only rational strategy is silence. But calling it a strategy implies a level of cool calculation that I do not think reflects the reality. It begins to look more like a trauma response.

The retreat into the Dark Forest is a form of digital PTSD. We are a population that has been over-exposed. We have lived through a decade where our social nervous systems were wired directly into a global feedback loop of outrage. We learned, through repeated shocks, that the open web is not an idyll meadow. We learned that context collapses instantly when exposed to the air of the timelin and an in-joke for ten friends can be weaponized by ten thousand strangers.

And so, we flee. Discord, Signal, paid newsletters et.al. We are building a network of internal worlds, spaces opaque to the outsider. Even if you have the invite link, even if you have backdoor access, you often cannot understand the culture within because it is built on a shared, emergent language of inside jokes, layered references, and tacit understanding. It is a return to the village, but a village built inside a bunker.

This opacity is an architectural necessity. In the open plain of the feed, time is flattened and everyone holds on to the now. A tweet from 2012 is dredged up to destroy a person in 2024 because the platform treats all data as simultaneously present. But in the thicket of the Dark Forest, time moves differently. It moves at the speed of trust. Conversations can meander for weeks. Ideas can be tested without the fear that they will be permanently recorded on a permanent record of moral failure.

The thicket is a blueprint for the emergent architecture of resistance. It suggests that the only way to survive High-Tech Modernism is to become unsearchable. To build structures that are so dense with local context, so high-friction, that the crawler cannot index them and the mob cannot parse them. It is here, in the shadows, that the fox begins to remember how to move.

IV. Homo Ludens and the Magic Circle

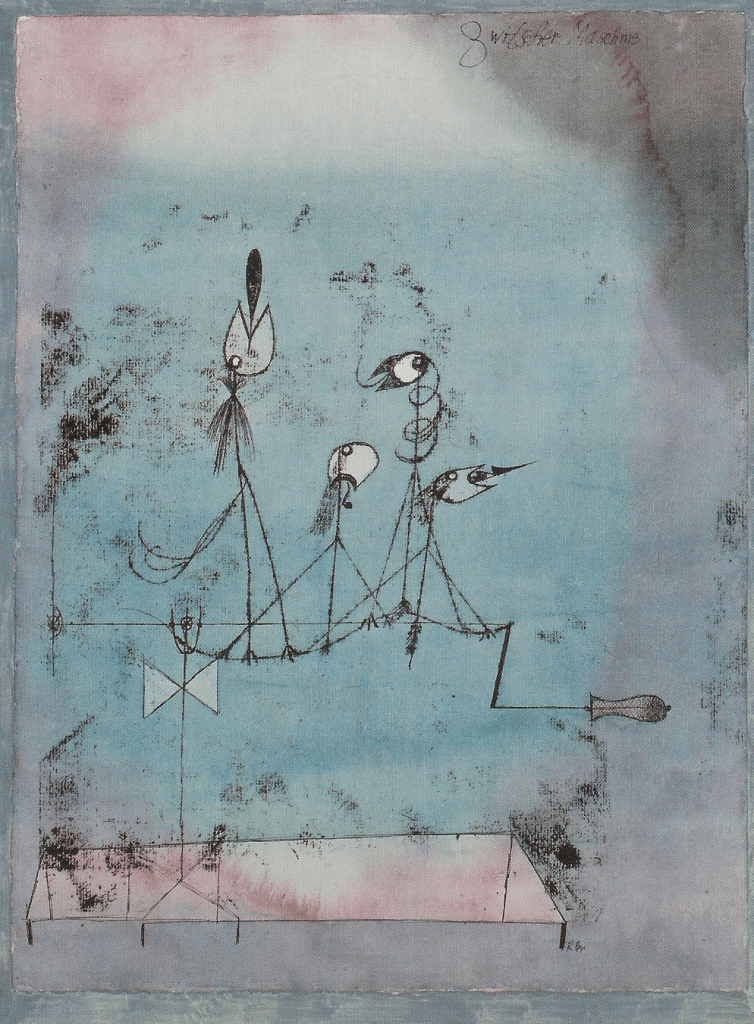

What the fox is looking for in the dark is not just safety. It is looking for the possibility of play. And we must be very careful here to distinguish play from what the internet has offered us. The internet has offered us gamification, which is the opposite of play.

Johan Huizinga, in his seminal work Homo Ludens, argued that play is older than culture. It is a distinct mode of being, separated from ordinary life by a Magic Circle. Inside the circle, the rules of the everyday world—the rules of utility, of profit, of survival—are suspended. We play not to achieve an outcome, but for the sake of the playing itself. Play is autotelic. It is its own justification.

Gamification, as the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen has brilliantly argued, is the invasion of the economic logic of the ordinary world into the realm of play. It is the imposition of Value Capture. When we gamify our reading habits (Goodreads), our exercise (Strava), or our social interactions (Twitter/X). We are laboring under a metric that has been imposed from the outside. We are chasing a score. Gamification takes the rich, subtle values of human life—the joy of a run, the insight of a book, the warmth of a conversation—and replaces them with a quantified, simplified proxy.

The fox knows the difference. The fox knows that the moment you start playing for the score, you have ceased to be free. You have become a function of the game designer. The professional was once beholden to the corporate ladder, now the creator is the ultimate victim of this capture. They must optimize their content. They must feed the beast. They have turned their curiosity into a job, and in doing so, they have exiled themselves from the Magic Circle.

The thicket, then, is an attempt to reconstruct the Magic Circle. It is a space where we can return to the Homo Ludens style of play. In the Dark Forest, we can waste time. We can pursue a line of inquiry that has no market value. We can write a three-thousand-word essay on the history of the buttonhook, or foxes in Bali, simply because its fascinating.

This return to play is not a retreat from seriousness; it is the precondition for serious thought. Huizinga noted that civilization arises and unfolds in and as play. New forms of thought, new institutions, and new possibilities do not emerge from the grim efficiency of the achievement subject. They emerge from the slack of the playful mind. The fox, playing in the dark, is not just hiding; it is generating the seeds of the next culture.

V. The Dilettante’s Revenge

This brings us to the figure of the Dilettante. In our professionalized, credentialed world, dilettante is an insult. It implies superficiality and, gasp, no commitment. Dilettante comes from the Italian dilettare—to delight. A dilettante is one who delights. A dilettante is an amateur—from the Latin amator, a lover.

The professional does it for money, for status, for the institution. The amateur does it for love. And in a world where the professionals have been captured by achievement games, where the experts are often just high-functioning hedgehogs trapped in their own narrow silos, it is the amateur who retains the capacity to see the whole.

The fox is the archetype of the Dilettante. The fox knows many things. The fox does not respect the boundaries of the disciplines. The fox does not care that historians don’t talk to biologists. The fox drags its long tail through the dust of the archives, picking up burrs and seeds from a dozen different fields.

It is this long tail that is the fox’s secret weapon. In the statistical sense, the Long Tail refers to the vast number of niche products or ideas that exist away from the head of the power law distribution. The head is the mainstream—the viral hits, the bestsellers, the trending topics. The head is where the algorithm points everyone. It is the realm of the Average. It is the terraformed plain of the Gunpowder Empire.

But the fox lives in the Long Tail. The fox is interested in the obscure, the forgotten, the largely ignored. Because the fox is playing for selfish satisfaction, they are free to pull from this vast reservoir of unmonetized knowledge. They can connect the structure of a 12th-century monastery to the architecture of a decentralized file system. They can see the parallel between the immune system of a rubber tree in the Amazon and the moderation policies of a Mastodon instance.

This combinatorial creativity is only possible for the Dilettante. The Specialist is too busy defending their turf to wander into the neighbor’s garden. The Specialist is suffering from Value Capture—optimizing for citations within their specific sub-field. The Dilettante, unburdened by the need to succeed in the conventional sense, is free to fail, free to wander, and free to find the strange, glowing fungi that only grow in the deepest parts of the thicket.

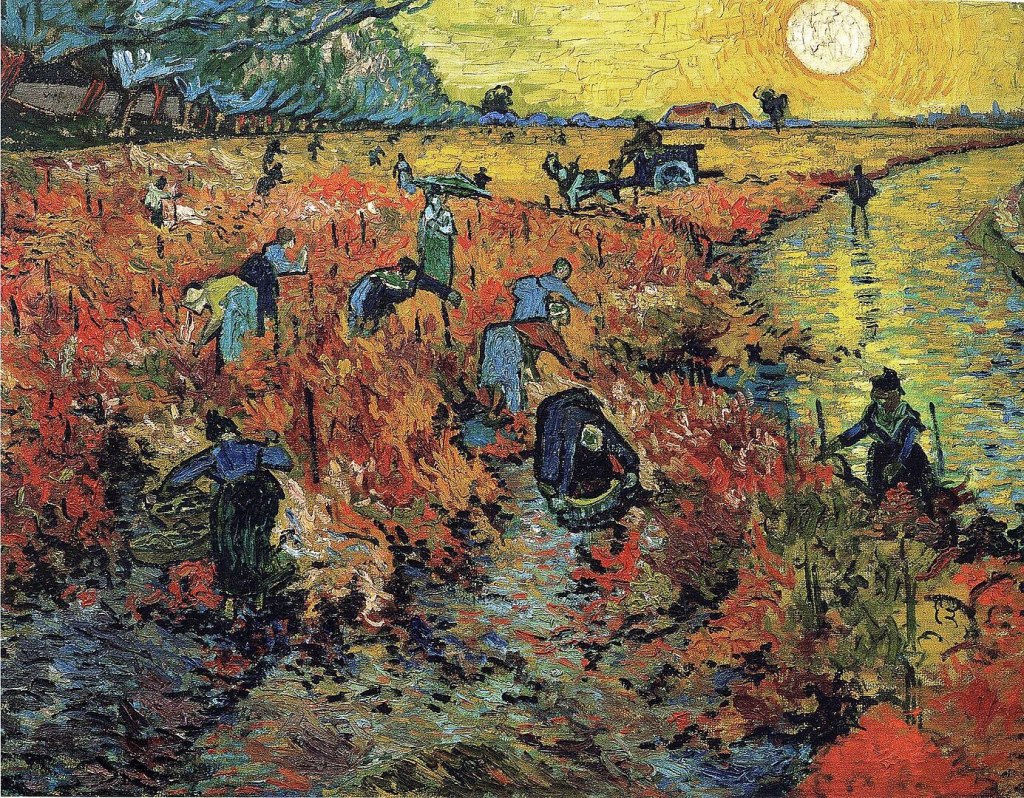

The thicket is the habitat of the Dilettante. It is a terroir of the mind. Just as a vine needs a specific soil, a specific slope, and a specific micro-climate to produce a great wine, the human mind needs a specific terroir to produce great thoughts. You cannot mass-produce terroir. You cannot scale it. It is local. It is inefficient. It is slow. And that is exactly why it is valuable.

VI. Writing as Dwelling – Selfish Writing

So, how does the fox learn to play? What is the practice?

Monsieur Montaigne did not write to teach the world. He explicitly warned the reader in his preface: “I have no thought of serving either you or my own glory… I have dedicated it to the private convenience of my relatives and friends.” He wrote, ostensibly, for selfish reasons. He wrote to paint himself.

We need to recover this selfishness. We should write for ourselves. We should write to find out what we think. We should write to build a dwelling for our own minds.

In the post Books are dwellings, I touched on this idea that reading is a form of inhabiting a space. Writing is the act of building that space. When we write for an audience, we are building a stage set. We are building a facade that looks good from the street but has no structural integrity. When we write for ourselves, we are building a home. We are laying bricks that can withstand the weight of our own contradictions.

This selfish writing is the ultimate resistance to the attention economy. When we write for the market, we are smoothing ourselves out. We are sanding down our rough edges to fit into the slot. We are becoming searchable. When we write for ourselves, we are cultivating our own terroir. We are allowing the brambles of our idiosyncrasies to grow. We are becoming a thicket.

To be a fox with a long tail in the dark forest is to accept a certain level of obscurity, in exchange, you get your mind back. Bringing something back, reporting from your thicket and reading others’ reports enriches the world. So, we should create, we should write. We should write for selfish reasons because this metabolic selfishness is the only thing saving us from the smoothened mean. We must reclaim the right to be outliers, to be amateurs. Us foxes must play.