-

How the Fox with the Long Tail Learned to Play in the Dark Forest

I. Everything is a Balinese Cockfight

It was after a police chase and a conspiratorial lie that Clifford Geertz and his wife Hildred were accepted into the social fabric of 1958 Bali. Until then they had been ignored, a treatment reserved for intruders. The police chase was the aftermath of attending a cockfight recorded in Geertz’ essay, Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight. The cockfight, a ritual with the stakes so irrationally high that they ceased to be about money (or the birds) at all. Status, dignity, and the honor of their kinship groups was all on the table. It was deep play—a game where the potential for loss so catastrophic, and the potential for glory so fleeting, that from a utilitarian perspective, it was madness to engage in it at all.

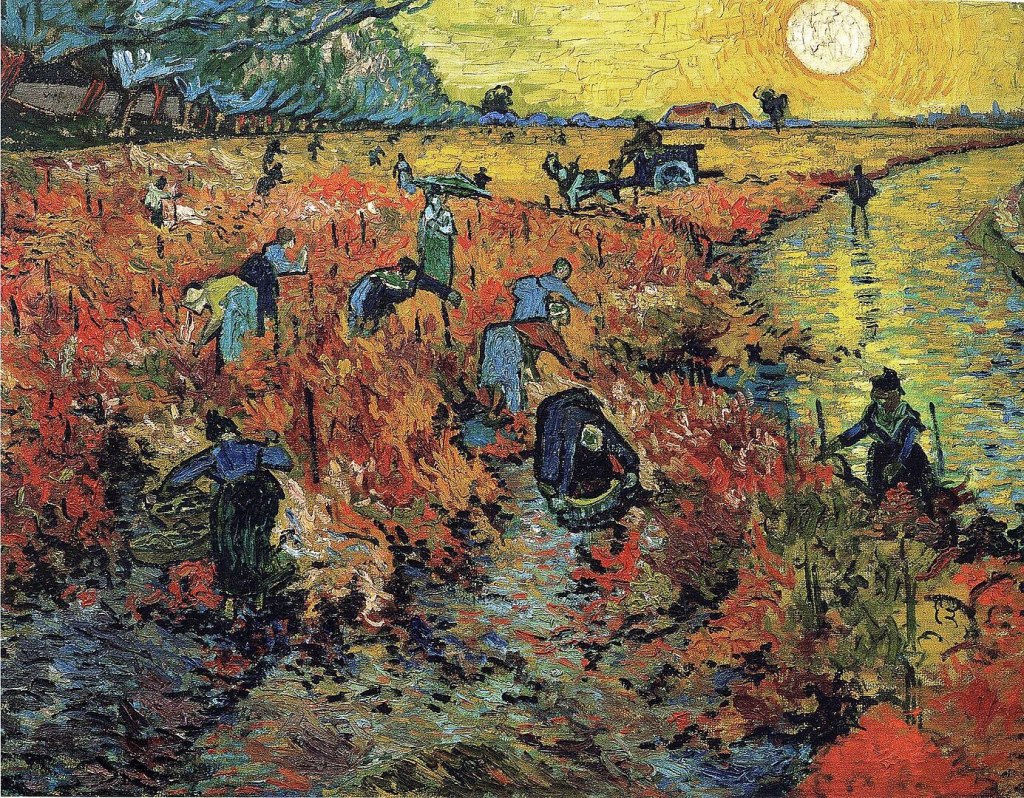

Foxes by Bruno Liljefors We have built a global version of this village. If one looks at the architecture of our current digital existence, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that we are all, perpetually, standing around the ring of a Balinese cockfight. Preparing and shaping our identities for the battle box of social media. Every post is immediate participation with unbelievably high stakes. Social media is place to bet on one’s own standing in the hierarchy. We have gamified human interaction to such a degree that the simple act of being has been replaced by the exhausting labor of performing.

This is why the silence has descended. It is not that we have nothing to say, but that the cost of saying it has outstripped the value of the connection. When every interaction is a deep play scenario the rational response is to stop playing. The open web, once promised as a boundless library or a global town square, has revealed itself to be a panopticon where the guards are also the prisoners, and everyone is armed with a scorecard.

The tragedy of this arrangement is not just the anxiety it produces, though that is significant. The tragedy is the loss of the middle layer of human experience. Geertz noted that the cockfight was a dramatization of status concerns, a way for the Balinese to tell a story about themselves to themselves. In our digital translation of this ritual, we have similarly flattened the world. The fox, an animal defined by its ability to navigate the undergrowth and find hidden paths, cannot survive in the center of the ring. The ring is designed for the hedgehog—the creature who knows one big thing and defends it with bristles. And so, the fox looks at the high-walled arena, sees the blood on the sand, and quietly slips away toward the tree line.

II. The Gunpowder Empire of the Mind

To understand why the open plain has become uninhabitable, we must look backward to the last time the world was reorganized by a sudden explosion of reach. Historians speak of the Gunpowder Empires—the Ottomans, the Safavids, the Mughals—who used the new technology of artillery to consolidate vast territories under a central authority. This required an administrative transformation. Gunpowder required money, and money required the translation of land into a legible, taxable asset. The loose, overlapping rights of the medieval village—where one man might own the fruit of the tree, another the right to graze beneath it, and a third the right to cross the field—were swept away. The state needed to know who owned what, exactly, so it could extract its due. Land became an abstract asset, a polygon on a map that could be bought, sold, and taxed without anyone ever touching the soil.

We are living through the rise of the Gunpowder Empires of the Mind, a new nature. Just as the early modern states needed to simplify the land to tax it, the High-Tech Modernist platforms of Silicon Valley need to simplify thought to monetize it. They are engaged in a project of radical legibility. A wandering thought is of no value to an algorithm since it cannot be categorized. A complex relationship is inefficient and creates friction in the social graph.

This is the war between Metis and Techne, a distinction drawn by the political anthropologist James C. Scott and the philosopher Isaiah Berlin. Techne is the knowledge of the system-builder, measured and protocolized. Techne is the language of the algorithm. It assumes that the world is a stable set of variables that can be optimized. It is the worldview of the Hedgehog, who relates everything to a single central vision—in this case, the vision of engagement metrics and ad revenue.

Metis, on the other hand, is the knowledge of the Fox. It is cunning, local, and slippery. It is the knowledge of the sailor who knows how to read the ripples on the water to find the current, or the peasant who knows which patch of soil stays wet longest in a drought. Metis cannot be simplified into a manual or a code base because it is dependent on the specific, shifting context of the now. It survives in the thicket—the messy, unmapped reality of lived experience.

The Gunpowder Empires of the Mind have declared war on Metis. They seek to pave over the thicket to create a smooth, frictionless plain where data can flow unimpeded. They want us to be Hedgehogs—consistent, predictable, and branded. They ask us to niche down, to define our vertical, to become thought leaders in a specific domain. They are trying to turn the messy ecology of human curiosity into a plantation of cash crops. The fox, with its long tail dragging through the mud of a thousand different interests, finding connections between a 17th-century poem and a 21st-century software bug, is an error in their system. The fox is illegible. And because it is illegible, it is being hunted.

III. The Dark Forest as a PTSD Response

It is no wonder, then, that we see a mass migration away from the center. Yancey Strickler and others have called this the Dark Forest Theory of the Internet, borrowing from Liu Cixin’s sci-fi axiom that in a universe full of predators, the only rational strategy is silence. But calling it a strategy implies a level of cool calculation that I do not think reflects the reality. It begins to look more like a trauma response.

The retreat into the Dark Forest is a form of digital PTSD. We are a population that has been over-exposed. We have lived through a decade where our social nervous systems were wired directly into a global feedback loop of outrage. We learned, through repeated shocks, that the open web is not an idyll meadow. We learned that context collapses instantly when exposed to the air of the timelin and an in-joke for ten friends can be weaponized by ten thousand strangers.

And so, we flee. Discord, Signal, paid newsletters et.al. We are building a network of internal worlds, spaces opaque to the outsider. Even if you have the invite link, even if you have backdoor access, you often cannot understand the culture within because it is built on a shared, emergent language of inside jokes, layered references, and tacit understanding. It is a return to the village, but a village built inside a bunker.

This opacity is an architectural necessity. In the open plain of the feed, time is flattened and everyone holds on to the now. A tweet from 2012 is dredged up to destroy a person in 2024 because the platform treats all data as simultaneously present. But in the thicket of the Dark Forest, time moves differently. It moves at the speed of trust. Conversations can meander for weeks. Ideas can be tested without the fear that they will be permanently recorded on a permanent record of moral failure.

The thicket is a blueprint for the emergent architecture of resistance. It suggests that the only way to survive High-Tech Modernism is to become unsearchable. To build structures that are so dense with local context, so high-friction, that the crawler cannot index them and the mob cannot parse them. It is here, in the shadows, that the fox begins to remember how to move.

IV. Homo Ludens and the Magic Circle

What the fox is looking for in the dark is not just safety. It is looking for the possibility of play. And we must be very careful here to distinguish play from what the internet has offered us. The internet has offered us gamification, which is the opposite of play.

Johan Huizinga, in his seminal work Homo Ludens, argued that play is older than culture. It is a distinct mode of being, separated from ordinary life by a Magic Circle. Inside the circle, the rules of the everyday world—the rules of utility, of profit, of survival—are suspended. We play not to achieve an outcome, but for the sake of the playing itself. Play is autotelic. It is its own justification.

Gamification, as the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen has brilliantly argued, is the invasion of the economic logic of the ordinary world into the realm of play. It is the imposition of Value Capture. When we gamify our reading habits (Goodreads), our exercise (Strava), or our social interactions (Twitter/X). We are laboring under a metric that has been imposed from the outside. We are chasing a score. Gamification takes the rich, subtle values of human life—the joy of a run, the insight of a book, the warmth of a conversation—and replaces them with a quantified, simplified proxy.

The fox knows the difference. The fox knows that the moment you start playing for the score, you have ceased to be free. You have become a function of the game designer. The professional was once beholden to the corporate ladder, now the creator is the ultimate victim of this capture. They must optimize their content. They must feed the beast. They have turned their curiosity into a job, and in doing so, they have exiled themselves from the Magic Circle.

The thicket, then, is an attempt to reconstruct the Magic Circle. It is a space where we can return to the Homo Ludens style of play. In the Dark Forest, we can waste time. We can pursue a line of inquiry that has no market value. We can write a three-thousand-word essay on the history of the buttonhook, or foxes in Bali, simply because its fascinating.

This return to play is not a retreat from seriousness; it is the precondition for serious thought. Huizinga noted that civilization arises and unfolds in and as play. New forms of thought, new institutions, and new possibilities do not emerge from the grim efficiency of the achievement subject. They emerge from the slack of the playful mind. The fox, playing in the dark, is not just hiding; it is generating the seeds of the next culture.

V. The Dilettante’s Revenge

This brings us to the figure of the Dilettante. In our professionalized, credentialed world, dilettante is an insult. It implies superficiality and, gasp, no commitment. Dilettante comes from the Italian dilettare—to delight. A dilettante is one who delights. A dilettante is an amateur—from the Latin amator, a lover.

The professional does it for money, for status, for the institution. The amateur does it for love. And in a world where the professionals have been captured by achievement games, where the experts are often just high-functioning hedgehogs trapped in their own narrow silos, it is the amateur who retains the capacity to see the whole.

The fox is the archetype of the Dilettante. The fox knows many things. The fox does not respect the boundaries of the disciplines. The fox does not care that historians don’t talk to biologists. The fox drags its long tail through the dust of the archives, picking up burrs and seeds from a dozen different fields.

It is this long tail that is the fox’s secret weapon. In the statistical sense, the Long Tail refers to the vast number of niche products or ideas that exist away from the head of the power law distribution. The head is the mainstream—the viral hits, the bestsellers, the trending topics. The head is where the algorithm points everyone. It is the realm of the Average. It is the terraformed plain of the Gunpowder Empire.

But the fox lives in the Long Tail. The fox is interested in the obscure, the forgotten, the largely ignored. Because the fox is playing for selfish satisfaction, they are free to pull from this vast reservoir of unmonetized knowledge. They can connect the structure of a 12th-century monastery to the architecture of a decentralized file system. They can see the parallel between the immune system of a rubber tree in the Amazon and the moderation policies of a Mastodon instance.

This combinatorial creativity is only possible for the Dilettante. The Specialist is too busy defending their turf to wander into the neighbor’s garden. The Specialist is suffering from Value Capture—optimizing for citations within their specific sub-field. The Dilettante, unburdened by the need to succeed in the conventional sense, is free to fail, free to wander, and free to find the strange, glowing fungi that only grow in the deepest parts of the thicket.

The thicket is the habitat of the Dilettante. It is a terroir of the mind. Just as a vine needs a specific soil, a specific slope, and a specific micro-climate to produce a great wine, the human mind needs a specific terroir to produce great thoughts. You cannot mass-produce terroir. You cannot scale it. It is local. It is inefficient. It is slow. And that is exactly why it is valuable.

VI. Writing as Dwelling – Selfish Writing

So, how does the fox learn to play? What is the practice?

Monsieur Montaigne did not write to teach the world. He explicitly warned the reader in his preface: “I have no thought of serving either you or my own glory… I have dedicated it to the private convenience of my relatives and friends.” He wrote, ostensibly, for selfish reasons. He wrote to paint himself.

We need to recover this selfishness. We should write for ourselves. We should write to find out what we think. We should write to build a dwelling for our own minds.

In the post Books are dwellings, I touched on this idea that reading is a form of inhabiting a space. Writing is the act of building that space. When we write for an audience, we are building a stage set. We are building a facade that looks good from the street but has no structural integrity. When we write for ourselves, we are building a home. We are laying bricks that can withstand the weight of our own contradictions.

This selfish writing is the ultimate resistance to the attention economy. When we write for the market, we are smoothing ourselves out. We are sanding down our rough edges to fit into the slot. We are becoming searchable. When we write for ourselves, we are cultivating our own terroir. We are allowing the brambles of our idiosyncrasies to grow. We are becoming a thicket.

To be a fox with a long tail in the dark forest is to accept a certain level of obscurity, in exchange, you get your mind back. Bringing something back, reporting from your thicket and reading others’ reports enriches the world. So, we should create, we should write. We should write for selfish reasons because this metabolic selfishness is the only thing saving us from the smoothened mean. We must reclaim the right to be outliers, to be amateurs. Us foxes must play.

-

The Deep Dark Terroir of the Soul

This is the third and final part of the Thicket Series:

Part 1: Logic of the Thicket and the Unsearchable Web

Part 2: The Architecture of Resistance

The history of the working subject might be best understood not as a ledger of wages or a sequence of industrial breakthroughs, but as a study in the migration of the Master. In the eighteenth century, the Master was a concrete presence, a figure residing in the castle or the cathedral, distinct from the worker by a physical and social chasm. One knew where the authority lived because one could see the smoke from its chimneys. By the nineteenth century, this figure had moved into the factory office, closer to the rhythm of the machine but still identifiable by the suit and the watch. The twentieth century saw a further dissolution; the Master became atmospheric, blending into the very walls of the institutions that housed us—the schools, the hospitals, the barracks.

And yet, it is in the twenty-first century that we witness the final and perhaps most unsettling migration. The Master has moved inside. It has taken up residence within the worker’s own mind, adopting the voice of the ego and the language of self-optimization. This internal migration has fundamentally altered the nature of exhaustion, shifting it from the physical depletion of the muscle to a profound infarction of the soul. To understand how we might resist such an intimate occupation, we must trace the lineage of this fatigue, moving from Voltaire’s eighteenth-century refuge of the Garden to the contemporary diagnosis of the Burnout Society, and finally, to an emerging architecture of resistance that might be called the Logic of the Thicket.

Felsenlandschaft im Elbsandsteingebirge Caspar David Friedrich1822/1823 The story begins in 1759, amid the wreckage of a world governed by grand, often violent, narratives. When Voltaire published Candide, the prevailing philosophical mood was one of forced optimism. Leibniz had posited that we lived in “the best of all possible worlds,” a claim that felt increasingly like a cruel joke to those living through the arbitrary brutalities of the era—the Lisbon earthquake, the Seven Years’ War, and the relentless inquisitions of both church and state. For the subject of the 1700s, the Master was external and undeniable. Life was a sequence of calamities administered from above.

In the final pages of Candide, after a lifetime spent traversing a world of rape, slavery, and disaster in search of Leibnizian meaning, the protagonist reaches a quiet, radical conclusion. He rejects the grand debates and the lofty theorizing of his companions with a simple, grounded imperative: Il faut cultiver notre jardin—we must cultivate our garden.

At this historical juncture, the Garden was more than a hobby; it was a strategy of containment. It served as a physical and psychological wall against a world that had grown too chaotic to manage. Voltaire suggested that simple, manual labor was the only effective shield against the primary threats of the human condition, which he identified as the Three Evils: Boredom, Vice, and Need. In the Garden, work was a form of retreat. It solved the problem of Need by providing physical sustenance—potatoes and produce—at a time when biological survival was never guaranteed. It addressed Boredom by occupying the hands and the mind with the repetitive, rhythmic care of the earth, saving the worker from the existential dread of idleness. And it warded off Vice by providing a sanctuary from the moral decay of the court and the city, replacing political intrigue with the honest friction of the soil.

The Garden was a place of safety because it was bounded. To work was to narrow one’s world to the reach of one’s own hands, creating a small, controllable private sphere where the Master’s voice was, for a moment, silenced by the sounds of the harvest.

However, this sanctuary could not withstand the arrival of the steam engine. As the nineteenth century progressed, the Garden was paved over by the Factory. The peasantry was pulled from the land and funneled into the burgeoning cities, where the nature of labor underwent a violent transformation. Karl Marx, observing this shift, identified the collapse of Voltaire’s dream. In the industrial setting, the worker could no longer cultivate a garden because they owned neither the seeds nor the harvest. They did not even own their own time.

This was the era of Coercion. Marx’s diagnosis of Alienation described a worker severed from the product of their labor, from the act of production, and from their own Gattungswesen, species-essence. The Master was now the Capitalist, and exhaustion was a physical reality—a depletion of calories and muscle. Resistance, accordingly, was also physical: the strike, the riot, the seizure of the machine. The goal was to reclaim the physical Garden that had been stolen.

As we moved into the twentieth century, the nature of control shifted again. Physical coercion, while effective, was inefficient; it bred visible resentment and the constant threat of revolution. Systemic power realized it was far more effective to train workers to police themselves. Michel Foucault described this as the Disciplinary Society, where the factory model was replicated across all social institutions. The governing logic became the Panopticon—the internalized gaze. The worker of this era was a docile body, governed by the operating verb Should. You should be on time; you should follow procedure. While the Master was becoming more abstract—a set of norms rather than a man in a tall hat—the enemy was still technically outside. There was still a door one could walk through at the end of a shift.

The true transformation occurred at the turn of the twenty-first century, a transition captured with clinical precision by Byung-Chul Han. Han argues that the Disciplinary Society has collapsed, replaced by the Achievement Society. The modal verb has shifted from Should to Can. The demand is no longer “You must obey,” but “Yes, you can.”

This shift has proven catastrophic for the psyche. In the old world of coercion, there was a limit; when the shift was over, the worker was, in a sense, free. But in the Achievement Society, the worker is an “entrepreneur of the self.” We are no longer exploited by an external boss so much as we exploit ourselves. We voluntarily work eighty hours a week not because of a threat of the lash, but because of a desire to “optimize” our personal brands and “reach our potential.”

The Master has completed its migration. We carry the Panopticon in our pockets and in our egos. In this state, the Garden is no longer a retreat; it has become a performance stage. We still cultivate, but we do so frantically, documenting the process for the digital gaze, tracking our productivity metrics, and feeling a gnawing guilt that our harvest isn’t as aesthetic or impactful as our neighbor’s. The boundary between the private and the public has dissolved into a smooth, legible –searchable– surface.

In this environment of total transparency, the Three Evils have mutated into contemporary monsters. Need is no longer about physical starvation; it has become Status Anxiety—the insatiable requirement for recognition and digital legibility. Boredom has been replaced by Hyper-Attention; we are never idle, but we are never at rest, trapped in a shallow, frantic multitasking that Han calls the “vice of the click.” And Vice itself has become Self-Exploitation—the auto-aggression of working oneself into a depression under the guise of self-fulfillment.

By 2024, the smoothness of our digital existence had become total. Silicon Valley had successfully turned the world into a frictionless landscape where data and capital flow without resistance. Algorithms now manage the Uber driver and the freelance coder alike, using gamification to nudge behavior through a mathematical black box. We have become Tourists in a digital world built by others, wandering through clean, well-lit interfaces that prioritize searchability, SEO, above all else. If a thing is legible, it can be indexed; if it is indexed, it can be exploited.

This brings us to the threshold of 2025 and the emerging response found in the Logic of the Thicket. If the Garden was a strategy of containment and the Factory was a site of coercion, the Thicket is a strategy of opacity.

A thicket is not a garden. It is messy, dense, and difficult to navigate. It does not possess the neat rows or the clear boundaries of Voltaire’s refuge. Instead, it is defined by friction. To resist the smoothness of the modern Achievement Society, the worker must transition from being a Tourist to being an Explorer. The Tourist consumes intelligibility—the ease of the app, the clarity of the interface. The Explorer, by contrast, generates place through the introduction of friction.

The Logic of the Thicket suggests that we cannot return to the eighteenth-century Garden. The walls are too brittle; databases will index the soil and an AI will recommend the fertilizer before the first seed is planted. Instead, the modern subject must create contexts that are unsearchable. This does not mean a total withdrawal from the world, but rather an engagement on terms that are too complex, too local, and too nuanced for an algorithm to easily optimize.

We might re-examine Voltaire’s Three Evils through the lens of this new architecture to see if the Thicket offers a viable path forward.

First, consider the evil of Need. In our current context, Need has become the fear of Irrelevance. In a smooth world, the worker is a standard, interchangeable part. If your work is legible—easy to measure and automate—you live in constant fear of economic obsolescence. This is the condition of the smooth professional: the software engineer whose code is indistinguishable from the output of a Large Language Model, the copywriter producing content that mirrors a thousand other blog posts, or the middle manager whose primary function is the transmission of standardized project plans. These roles are vulnerable because they lack friction; they offer no resistance to the efficiency of the machine.

The Thicket addresses this through the concept of Terroir. In the culinary world, terroir refers to the specific qualities of soil, climate, and tradition that give a wine or a cheese its unreplicable character. In the world of labor, terroir is the infusion of one’s work with local context, historical depth, and human idiosyncrasy.

For this blog, the terroir is found in the deliberate, often difficult work of communal deep-reading and historical synthesis. Here, history is not viewed as a sequence of headlines, but as a series of vast, slow-moving machines—intellectual contraptions that take centuries to build and even longer to fully start. By examining the past through this mechanical lens, the thinker begins to see the world not as a “smooth” stream of current events, but as a dense thicket of long-term trajectories.

The process behind this blog—reading deep into difficult texts, engaging in exhaustive discussions with other thinkers, and synthesizing these influences through a deliberate collaboration with artificial intelligence—is itself a “thick” form of labor. It is a method of finalizing thought that creates a durable value, one that cannot be mimicked by a prompt-engineered shortcut. By making your work “thick”—laden with specific references, local nuances, and the friction of deep thought—you make yourself un-automatable. The machine can navigate a smooth database, but it struggles to traverse a thicket of idiosyncratic human insights that are anchored in the deep time of historical machinery. The Thicket ensures survival not by making the worker more efficient, but by making them indispensable through their unique, unsearchable “friction.”

Next, the evil of Boredom has mutated into Passive Consumption. We are over-stimulated but spiritually idle, doom-scrolling through a world where nothing we do actually changes the environment. We are Tourists in the digital landscape, consuming the “intelligibility” of others. The Thicket solves this by demanding active navigation. In a world where algorithms predict what we want before we know it, the Thicket reintroduces the struggle of discovery. You cannot be “bored” when you are bushwhacking through a complex structure of your own making, or when you are trying to understand the slow grinding of a historical machine that began its first revolution centuries ago. The joy of the Thicket is the joy of the Explorer—the realization that the landscape is resisting you, and that you must exert agency to move through it.

Finally, Vice has become Algorithmic Complicity—the moral laziness of letting an interface decide who we speak to, what we read, and how we spend our time. It is the vice of “disindividuation,” allowing ourselves to be smoothed down into a demographic data point. The Thicket forces a return to Virtue through Agency. To build a thicket is to refuse to be effortlessly “known.” It requires the “virtue” of privacy and the patience of shared inquiry. A “network” is smooth; you connect with a click. A “community” is a thicket; it requires negotiation, trust, and the willingness to engage with the “messiness” of other people. It requires the slow effort to inhabit a text that refuses to be summarized by an executive summary or a bulleted list.

The journey from 1759 to 2025 is a circle that does not quite close. Voltaire’s worker fled the violence of kings into the Garden, seeking a physical retreat. Marx’s worker lost that garden and fought to reclaim the tools. Han’s worker internalized the factory, turning their own mind into a sweatshop of positivity. And the worker of 2025 now realizes that the mind itself has been mapped.

The only remaining escape is to leave the Garden—which has become a trap of transparency—and enter the Thicket. There is a critical difference here: the Garden was intended to be safe, but the Thicket is defensive. It is a posture for a hostile territory. It saves us from Boredom by making life difficult again. It saves us from Vice by requiring conscious choice rather than algorithmic default. And it saves us from Need by ensuring we remain human enough that the machines cannot find a way to replace the specific texture of our presence.

It is a harder path than the one Candide chose, but in a world where the Master lives in the code, it may be the only path left. The mandate for the contemporary soul is no longer simply to cultivate, but to grow something so dense and so deeply rooted that the algorithm, for all its processing power, simply cannot find the way in. We look toward the edge of the woods, not for a way out, but for a way to disappear into the depth of the growth.

Coda: The Machinery of the Thicket

This essay is not merely a reflection on labor; it is a byproduct of the very “Logic of the Thicket” it describes. To write it was to engage in a form of “thick” labor—a deliberate resistance to the high-speed, surface-level synthesis typical of the Achievement Society. Below is the intellectual architecture and the process that generated this piece.

The Conceptual Bedrock

The essay’s trajectory is built on a specific lineage of thinkers who have tracked the migration of power from the town square into the central nervous system:- Voltaire (Candide, 1759): Provides the initial defensive posture—the Garden. His “Three Evils” (Boredom, Vice, Need) serve as the recurring benchmarks for human exhaustion.1

- Karl Marx: Used here to mark the collapse of the private garden. The transition from Sustenance to Alienationis the first great rupture in the history of the working subject.

- Michel Foucault: His concept of the Disciplinary Society and the Panopticon explains how the Master became “atmospheric.” It is the era of the “Should.”

- Byung-Chul Han (The Burnout Society): The pivotal contemporary influence. Han’s shift from the “Should” (Foucault) to the “Can” (Achievement) explains why modern exhaustion is an “infarction of the soul.”

- Yuk Hui: His work on Technodiversity and the “recursive” nature of history informs the transition from the Tourist to the Explorer. He suggests that we cannot escape technology, but we must diversify our localrelationship to it.

The Process: Generating “Terroir”

The writing of this piece followed a “thick” methodology designed to avoid the “smooth” output of standard digital content:

- Deep Reading as Resistance: Instead of relying on summaries, the process involved “bushwhacking” through the primary texts. This creates Friction—the slow realization of meaning that cannot be automated.

- Mechanical Synthesis: Viewing history as a series of Slow-Moving Machines. By treating the transition from the Printing Press to the LLM as a mechanical evolution rather than just “progress,” we can see the gears of authority shifting.

- Collaborative Friction (AI as a Grinding Stone): Rather than using AI to generate the text, it was used as a sparring partner to test the “thickness” of the ideas. If the AI could predict the next point too easily, the point was discarded as being “too smooth.”

- The Infusion of Local Context: The essay intentionally uses specific, non-indexable metaphors—like the Thicket and Terroir—to anchor the abstract philosophy in a visceral, earthy reality.

The Goal: The Unsearchable Life

The ultimate aim of this “Coda” is to encourage the reader to see their own intellectual life as a Terroir. The “Master in the code” thrives on standardized, legible data. By engaging in deep history, difficult synthesis, and private creation, you grow a thicket. You become a “place” that is too complex for a map, a subject that is too dense for an algorithm, and a worker whose exhaustion is finally, once again, your own.

-

The Architecture of Resistance

The seventeenth-century Hague, the mid-twentieth-century Levant, and the digital terraforming of 2025 have a shared preoccupation with the “Average.” Whether it is the theologian’s way or predictive stats, control begins by smoothing out the landscape. The project of power is a project of cartography and illumination—an attempt to banish the dark corners where the unmapped might grow. Thus, the history of resistance, of being “against the world”, is less a history of rebellion than a history of seeking cover.

The Large Piece of Turf, 1503 Albrecht Dürer In Spinoza’a world, legibility was the cosmos in an ordered hierarchy. Meaning descended from an external judge and was mirrored by the terrestrial proxy of the King and more often the priest. Behavior was aligned to the “Scriptural Average.” A pre-written behavioral code that transformed the conatus—that primal drive to persist and expand—into the passive states of hope and fear. By removing the external judge, Spinoza suggested that freedom is found in the intellectual mastery of the causes that move us. A pushback against the “average pious subject,” asserting that every individual is a necessary, logical expression of an infinite substance. There is no error in the world, only the lack of a thick enough understanding to perceive the necessity of one’s own outlier status.

With this position, and self assurance, Spinoza became illegible to his friends, his doting teacher, and his community. He was cast out, but his thoughts are the seeds of today’s world.

In the Beirut and Damascus of the mid-twentieth century, the imposition of legibility took the form of the “Citizen-as-Monument.” It was a world of endings, where identity was a frozen artifact of nationalist scripts and religious orthodoxies. The poet Adonis, through Mihyar, pushes against this world not by asserting a new identity, but through a “movement of erasure.” If a stable interior is to form, it is to be quickly discarded. A stable interior is merely another coordinate, a dependable predictor, for the state to map. Mihyar becomes a “knight of strange words,” defined by the iltifat—the sudden turn away. By peeling back the layers of the social mask and embracing a radical anonymity, he counters the stagnant city. He exists as a hot wind, something that is felt through its movement and friction, yet remains entirely unsearchable by the collective grammar.

We have entered a third world, a digital landscape that functions as a terraformed plain. It is, in a sense, a Spinozan monism—all data is one substance—but it is a substance managed by a Leibnizian bureaucracy of optimization. The mechanism of control is no longer the scripture or the state monument, but the “Mechanical Harmony” of the statistical mean. A decade ago this was social media shaping votes. Today’s AI tools, perhaps inadvertently and perhaps not, impose an “averageness” on thought itself, by providing the next likely response and hiding the outlier. This is a form of disindividuation disguised as efficiency, a smoothing of the world’s texture until it becomes a frictionless surface for the sake of searchability.

What emerges as a necessary response is the logic of the thicket. If the terraformed plain is the habitat of the tourist—where everything is predicted, optimized, and known—the thicket is the habitat of the explorer. It is a deliberate architecture of complexity, an insistence on terroir and the messy, non-replicable context of the local. To build a thicket is to re-introduce friction into a world too smooth. We are apes inhabiting the long tail. Like Spinoza, our conatus withers under the umbrella the statistical mean. If every response is predicted, the individual ceases to be a cause and becomes merely a consequence of the architecture.

To emerge, life itself needed discontinuities. The thicket provides the opacity necessary for the transforming process of the self to occur. It honors the uneven distribution of the world, providing a high-density environment of unique, complex encounters impossible in a flat plain. In this 2025 context, to be “against the world” is perhaps better understood as being a cultivator of these unsearchable spaces. The Dark Forest of the internet has created literal operating systems, habitats for our interconnected selves. Away from the violent imposition of the center, things can still happen by surprise. We seek cover in the thicket as a primal way of being where the emergent world remains deep enough to inhabit.

-

The Tortured Artist Is So Yesterday

41 years ago, Samuel Lipman wrote that an artist’s life is a “constant—and constantly losing—battle” against one’s own limits. That image has lasted because print culture taught us to imagine the artist as a solitary figure whose worth is measured by the perfection of a single, final work. Print fixed texts in place, elevated the individual author, and made loneliness part of the creative job description.

That world is slipping away.

And with it, the tortured artist.

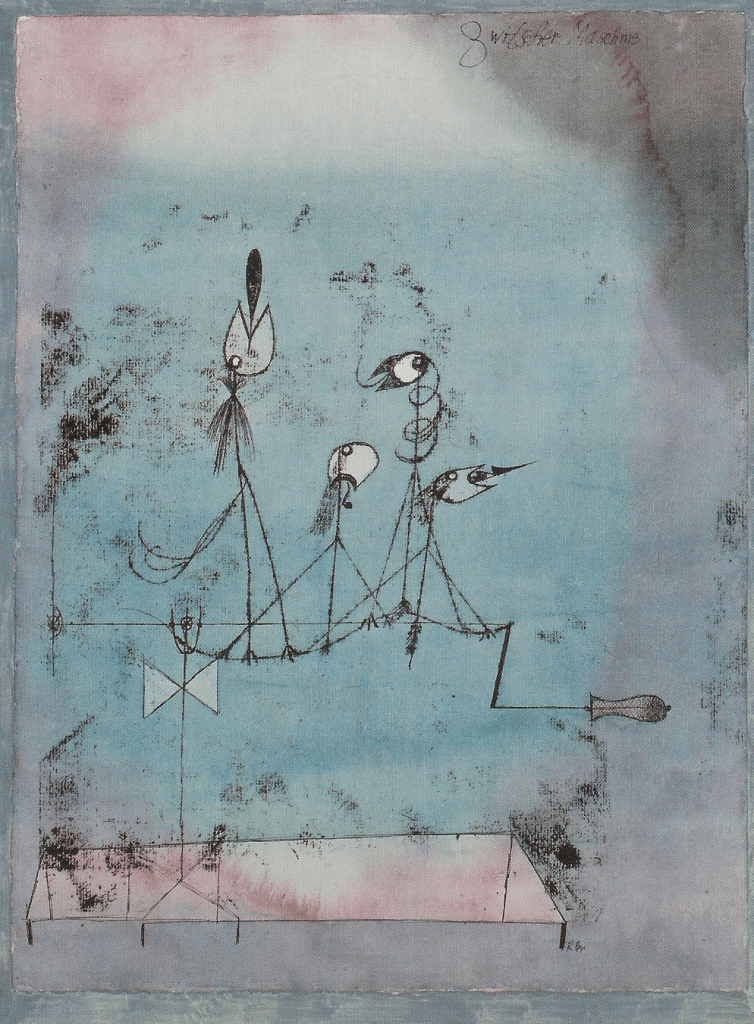

Twittering Machine (Die Zwitscher-Maschine) is a 1922 watercolor with gouache, pen-and-ink, and oil transfer on paper by Swiss-German painter Paul Klee LLMs have made competent expression abundant. The blank page no longer terrifies; anyone can produce something fluent and polished. When craft becomes cheap, suffering loses its meaning as a marker of artistic seriousness. What becomes scarce instead is the willingness to take a risk—not in private, but in public, where a stance can fail, provoke, or be reshaped by others.

Venkatesh Rao recently argued that authorship is no longer about labor but about courage: the courage to commit to a line of thought and accept the consequences of being wrong. In an era of infinite variations, the decisive act is not creation but commitment. The value lies in staking something of yourself on an idea that may not survive.

This shift is reshaping where culture is made. In what I’ve called the “Cloister Web,” people draft and explore ideas in semi-private creative rooms before carrying only a few into the open. LLMs make experimentation cheap; they also make commitment expensive. The hard part now is choosing which idea you are willing to be accountable for.

As the burden of execution drops, something else rises: genuine collaboration. Not just collaboration with models, but with other humans. Andrew Gelman, reflecting on Lipman in a recent StatModeling post, noted that scientists, too, feel versions of this pressure of the solitary creator. In science, the burden rarely falls on one person. The struggle is distributed across collaborative projects that outlive any single contributor.

Groups can explore bolder directions than any one creator working alone. Risk spreads, ideas compound, and the scale of what can be attempted expands. The solitary genius was an artifact of print; the collaborative creative lab is the natural form of the world we are entering.

This leads to a claim many will resist but few will be able to ignore: the single author is beginning to collapse as a cultural technology. What will matter in the coming decades is not the finished artifact but the evolving line of thought carried forward by teams willing to take risks together.

The tortured artist belonged to an age defined by scarcity, perfection, and solitude. Today’s creator faces a different task: to choose a risk worth taking and the collaborators worth taking it with. The work endures not because it is flawless, but because a group has committed to pushing it forward.

Pain is optional now.

Risk isn’t.

-

Four Early-Modern Tempers for a World That Can Summon Itself

This is a partial synthesis of the books read through 2025 in the Contraptions Book Club.

We live in a moment when the whole of human culture has become strangely available, no longer just an archive but something that behaves like a responding presence. A sentence typed into a search bar or messaging window returns citations and, more strikingly, continuations: pastiche, commentary, new variations of ideas that never existed until the instant we requested them. The canon now behaves more like a voice than a library. It is easy to treat this as convenience, yet summoning culture alters our relation to meaning in ways we are only beginning to see. The question is no longer whether we can find the relevant text, but what it means to think in a world that can generate its own echoes.

This instability has precedents in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Print multiplied texts; voyages multiplied worlds; the Reformation multiplied authorities. Four writers—Thomas More, Michel de Montaigne, Giordano Bruno, and Ibn Khaldun—stood at different corners of that era’s turbulence. Read from a certain angle, they reveal four temperaments that recur whenever the world grows larger and more articulate than before. They capture four ways of holding meaning in a world where frames widen and boundaries blur.

Their temperaments arose under the tension of two kinds of pressures. One pressure concerns frame: how much of the world a thinker attempts to hold in view. Another concerns form: how rigidly one tries to shape or preserve meaning in the face of flux. The tension between narrow and wide frames, between hard and soft forms, is a recurring feature of intellectual upheaval. It is with us again.

Northeaster (1895) by Winslow Homer. Original from The MET museum. Thomas More and the dream of designed simplicity

When More wrote Utopia, he was answering a world that felt newly disordered: economic enclosure, fracturing religion, unfamiliar continents, and the early tremors of what we now call modernity. His response was to shrink the frame to a bounded island and then remake that island according to simple, intelligible rules. Clothes are standardized; work is scheduled; houses interchangeable. Property, that generator of complexity, is abolished.

This gesture—the compression of a vast, unruly world into a legible miniature—reflects a deep conviction that the good life can be engineered by eliminating what does not fit the plan. Yet much of what makes human life livable emerges not from design but from the unplanned: the pleasure of choosing one’s clothes, improvising a routine, rearranging a room, wandering through a market whose wares no one fully controls. These small freedoms, these ambient textures, carry a kind of happiness that explicit blueprints rarely acknowledge. More’s island, for all its order, feels airless because it denies the subtle satisfactions of emergence.

We still see this impulse today, whenever we imagine that meaning will return if only we can simplify the world enough—reduce choices, curtail variation, enforce legibility. It is a refusal to accept that complexity is a problem to be solved only up to a point, beyond which it becomes the medium of human flourishing.

Montaigne and the work of making knowledge one’s own

Montaigne faced the same expansion of texts and reports, but his answer was almost the inverse of More’s. In his Essays, he turned the proliferating world into material for a sustained inquiry into a single life—his own. He narrowed the frame even further—not to an island but to a single life—and then allowed that life’s boundaries to loosen. His essays are records of a mind being changed by what it reads and observes. They are porous documents, absorbing classical quotations, passing impressions, and the texture of his shifting moods.

He described this process with the image of bees making honey: they gather from thyme and marjoram, but the result is neither; the ingredients have been transformed. Mere access to texts is not enough. The material must be digested until it becomes inseparable from the person who has absorbed it.

This is a temperament well suited to a world in which culture can speak back in any tone we request. The ease of access makes superficial familiarity almost effortless; the difficulty lies in allowing the material to ferment into something one can honestly call one’s own. Montaigne’s form is soft, because he does not impose a system on the world or on himself. He lets contradictions remain. His essays show what inward honesty looks like when the outer world has grown noisy.

Bruno: infinite worlds, unreliable memory

If Montaigne compresses the world into a single consciousness, Bruno explodes it. In works such as On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, he offered a speculative cosmology that pushed beyond the scientific imagination of his time. His universe is infinite, populated by innumerable worlds, animated by a universal divinity. These were not scientific inferences—they were imaginative leaps, metaphysical provocations in a period when the cosmological picture was coming loose.

Bruno’s response to the widened cosmos led him to enlarge the frame until it became boundless. Boundaries, for him, were treated as provisional, always liable to be surpassed. He was fascinated by memory—its limits, its artifices, its potential for augmentation. His elaborate mnemonic wheels were attempts to externalize thinking, to allow a mind to move through more space than it could otherwise hold.

There is something oddly familiar in this, not because our devices prove Bruno right, but because they echo his aspirations. We have built systems that externalize memory, recombine fragments, and present them as if they had always existed. These contrivances are not cosmic, yet they invite a cosmic mood—a sense that boundaries have thinned, that the archive stirs, that the mind can wander farther than it once could. Bruno illustrates the allure and the danger: the exhilaration of boundless possibility, and the risk of believing that imagination alone can stand in for contact with the world.

Ibn Khaldun and patterns at civilizational scale

Ibn Khaldun took the widening of the world seriously, but he kept his feet on the ground. In the Muqaddimah, his great introduction to history, he sketched a theory of how societies cohere, flourish, and decline. His frame is large—empires, dynasties, generations—yet his form is restrained. He offers no blueprint for an ideal state. He offers something closer to a natural history of political life: groups harden and cohere, conquer, soften, decay, and are replaced. Boundaries matter to him—the line between desert and city, between ruler and ruled—but they are not eternal. They shift, erode, reemerge.

His stance avoids both utopian control and ecstatic dissolution. It is descriptive, analytical, patient. He wants to see how things actually behave across time. In a world that now contains its own searchable memory and can generate plausible continuations of its past, this way of looking feels newly relevant. The swirl of events becomes legible only when placed against deeper patterns. Ibn Khaldun’s gift is to show that large frames can coexist with modesty of form.

Two diagonals

One can sense two lines running through these four positions. On one line are More and Bruno—the designer of tight enclosures and the dissolver of all enclosures. Both feel the shock of a world grown too large and respond by refusing its messiness: one by shrinking it to a legible fragment, the other by exploding it into a metaphysical totality. Both try to replace the world’s emergent complexity with a clarity of their own making.

The other line runs between Montaigne and Ibn Khaldun. Both accept that the world, whether at the scale of a single life or of a civilization, has a texture that cannot be fully captured by design or metaphysics. Both are interested in how things actually unfold, without forcing them into an ideal shape. Their frames differ—one intimate, one panoramic—but their attitude toward form is similar: let patterns emerge, let boundaries be porous enough to reveal movement, let humility guide description.

This second diagonal sits more naturally with a culture that can be summoned on demand. When the archive can answer back in endless variations, attempts to design simplicity or to dissolve all limits tend to fatigue. What remains workable is the inward practice of belonging to oneself and the outward practice of reading patterns without imagining them eternal.

Temper temper

We now inhabit a world in which knowledge behaves differently than any earlier generation anticipated. It can be queried, ventriloquized, recombined. This does not tell us how to live, but it changes the background against which living takes place. More’s dream of a perfectly designed order feels at once more possible and more implausible. Montaigne’s slow digestion of borrowed thought feels newly demanding. Bruno’s intoxication with boundlessness feels familiar, and Ibn Khaldun’s attention to cycles and decay feels newly sober.

These tempers recur whenever the world becomes more articulate than before. Ours is such a moment. We can now create stable points of reference with enough meaning and legibility to allow exploration of surrounding space. Print unlocked the beta version of this superpower. These four writers, shaped by the last great expansion of the world’s voice, find themselves speaking again through us, as we try to understand what it means to think with culture on tap.

-

favorite movies

Friend asked if Constantine was my favourite movie… I mean Neo and the librarian in one movie?? Yes please!

but… Not my favorite though… that would be between Notting Hill, The Mummy, and The Matrix. None of them are good movies — in the way that Perfect Days and sooo many others are — but they are my movies.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.